Yellow Tail Woolly Monkey

In 1974, Dr. Russell Mittermeier, Anthony Luscombe, and Hernando de Macedo saw a pet monkey in northern Peru. There were only 5 skins of this monkey in museum collections. Russell was stunned. It had dense red brown hair and yellow tail fur. The yellow-tailed woolly monkey (Oreonax flavicauda), that had been lost to science for over 100-years, was alive, and probably living in a forest somewhere nearby.

Dr. Antonio Brack, the supervisor of my bear research in Peru, put me together with primatologist Mariela Leo to find the yellow-tail, and then help establish a reserve for it. If found, it would be the largest mammal in Peru that is found nowhere else (endemic).

Over a period of several months in 1978, Mariela, Roberto Rodriguez, and I surveyed bears northward through the coastal desert, and then crossed over the Andes toward the jungle. By the time we arrived in Pedro Ruiz Gallo in the Department of Amazonas, we were badly shaken by rutted dirt roads.

There we met Daniel La Torre who claimed he had shot woolly monkeys he called “tupas” in a cloud forest a day’s journey on foot from a town above Pedro Ruiz.

On the way up the mountain we saw a yellow-tail stuffed with grass under the eaves of Toi Antenor’s (uncle thunder) house. This old man often went to the forest to collect fruit and was familiar with tupas. We hired him and another trail cutter to come with us.

Daniel took us to a cave where Tio Antenor promptly pounded bark off vines and wove them into baskets to hold the fruit he would harvest. We were left on our own to find the tupas.

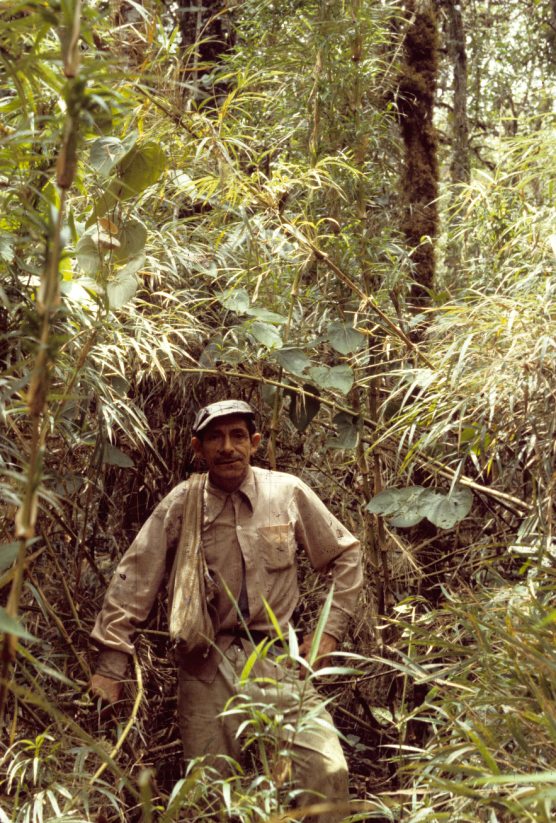

This is the type of jungle that Werner Hertzog called a “fornicating green hell, where even the birds scream in pain”. It is steep, clogged at all heights with bamboo, and soaking wet from meters of precipitation a year. One month of this was enough to give us trench foot for life. Our guides rolled cigarettes from the paper I had written my field notes on, and were about to consume the alcohol we needed to preserve plant specimens. We left after a week when all the coca leaf had been chewed. The trail cutters were out of the gasoline that kept them going.

After months of cloud forest trips, I began to appreciate what this one forest had, that the others seemed to lack. Fruit, and infrequent level ground where fruit trees grew to colossal size. We went back to Pedro Ruiz for another visit to the cave in the clouds. Another week of wet duff falling on our necks.

This time we saw three monkey species up to an elevation of almost 9,000-feet in the forest. The brown capuchin was large enough to be confused for tupas. It was a good sign. Clearly there was the right food to support yellow-tails. Figs, a Sapotaceae species, and something the guides called wild cherry.

We failed to find the elusive tupa during several more field trips. I was at the point of giving up hope of seeing a spectacled bear as well, although the scars of their claws on trunks were everywhere. On the 28th day in this forest we saw a rare sight. The rain stopped. Blue sky filled the gaps in the leaves, and water drops glistened. Then we heard barking and a crash off our trail. We followed Daniel as he dashed through underbrush. When we caught up with him, a male yellow-tail had descended to within 20 feet of us overhead. He was shaking branches and displaying blue testicles surrounded by yellow hair. Here was something lost to science, but very much in the conscience of Daniel. “Tupas”, he said matter -of-factly. I barely had time to assemble my camera and squeeze off a shot at a mother with child on her back, before they disappeared in tree tops.

Mariella dedicated her life to saving the remaining populations she found here and in very few mountain ranges nearby. There is now a park (Cordillera de Colon National Sanctuary) near where we saw our first yellow-tail. And Daniel, the tupa hunter, became an ardent spokesman in the region for their survival. At roughly nine pounds, the yellow-tail woolly monkey is the largest endemic mammal in Peru, meaning it has not been found in any other country.