Destiny of bears and people intertwined

The story of what has happened to populations of spectacled bears in the Andes since the 1960s is grim, but also sprinkled with promising developments. None the least of which is the quintupling of the national park system in 5 Andean countries with spectacled bears (eg., Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia). I have been a part of that effort, as the first field researcher to do significant studies of spectacled bears in the wild (1977-1984), and later as a coordinator of bear conservation (Co-Chair IUCN Bear Specialist Group and Secretary of the International Association for Bear Research and Management).

I arrived in Peru in August 1977 knowing only a few words of Spanish and having had only a few months of training as a bear biologist. When I left in 1998, I had two graduate degrees and knew one thing. Spectacled bears need the same resources as humans, and both species were in dire trouble due to the removal of forests. If the loss of bears could advertise the need to maintain forests, people would be the major beneficiaries. Here is how the destiny of bears and people are intertwined.

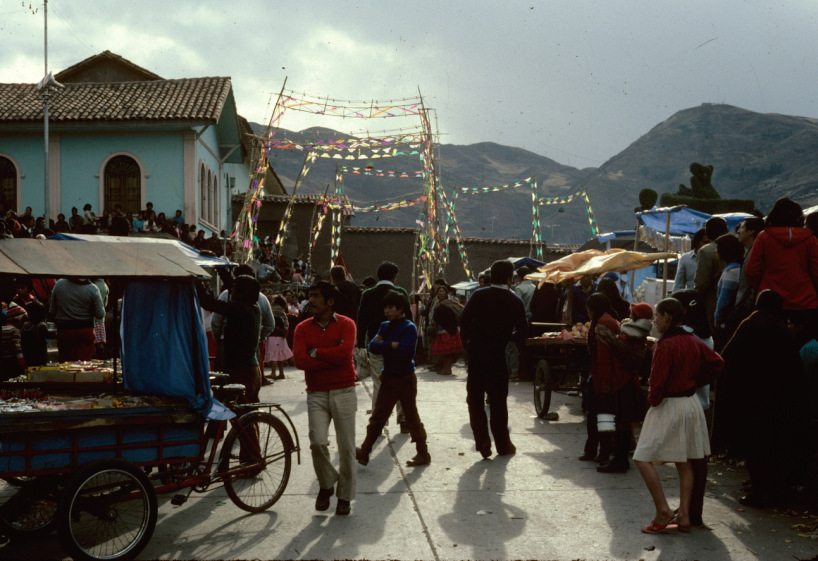

In the 1950s, 2-5% of the human population in the Andean nations owned 60-80% of all arable land. The inequitable land distribution and the growing families of peasant farmers forced them in the 1960s to abandon their crop fields and head for cities with hopes to join the industrial class. This was no small exodus from rural to urban areas. For example, one quarter of Peru’s population was mobile in 1962. The severity of unequal land ownership is one reason why South and Central American countries have the highest percentage of their people living in urban areas. This places tremendous pressure on rural inhabitants to supply the cities with their resource needs.

Once in cities, peasants were denied the education and upward mobility they sought. City mayors were scared that the rapid influx of people into their cities would cause insurrection. With the help of development agencies such as US AID, roads were built from coastal and highland metropolises to the jungle in part to relieve overpopulated cities.

In the 1970s, some recent immigrants to the cities went toward the jungle but stayed in the inter-Andean valleys to farm. This area is known by the colorful term “ceja de selva” or “eyebrow of the jungle”. Although capable, farmers had to learn how to farm the ceja in a sustainable manner.

The work of clearing fields and harvesting crops on steep vegetated slopes was exhausting and dangerous. The fore foot of this farmer’s horse had punched through suspended roots on a trail causing a compound fracture. My guide Melanio Quispe made a splint with padding from one of my socks to no avail. As it was during my research, crops and supplies in the ceja had to be carried on the backs of humans.

Slash and burn farming is sustainable when fallow periods are long enough for soil nutrients to recover. However, the kind of farming done in the ceja didn’t allow land to recover. When a crop field no longer could produce corn, it was planted in grass for livestock grazing. A new field was then cut upslope of the old one. In this way the cloud forest edge receded 100 meters with every crop rotation until the forest no longer existed.

Spectacled bears readily ate the corn that replaced their natural foods of wild figs and avocadoes. This raised the ire of farmers who killed and poisoned bears. Spectacled bears were safer from hunters in the dense forest, but vulnerable in the more open corn fields.

The extirpation of bear populations does more than remove bears. Wild avocadoes like the Nectandra species in the picture above grow to tremendous size in the cloud forest. Spectacled bears are the principle dispersal agent of the large stone seed of these trees.

The extent of forest removal in the ceja is catastrophic. Inter-Andean valleys up to a height of 2,500 -meters above sea level have had their forests removed throughout South America. Even national parks are not safe from deforestation.

The picture above shows a new field being cleared kilometers inside Cayambe-Coca Ecological Reserve in Ecuador. It was burned in the dry season to fertilize 3-4 years of crops. Eighteen years later that same area was transformed to the pasture shown below.

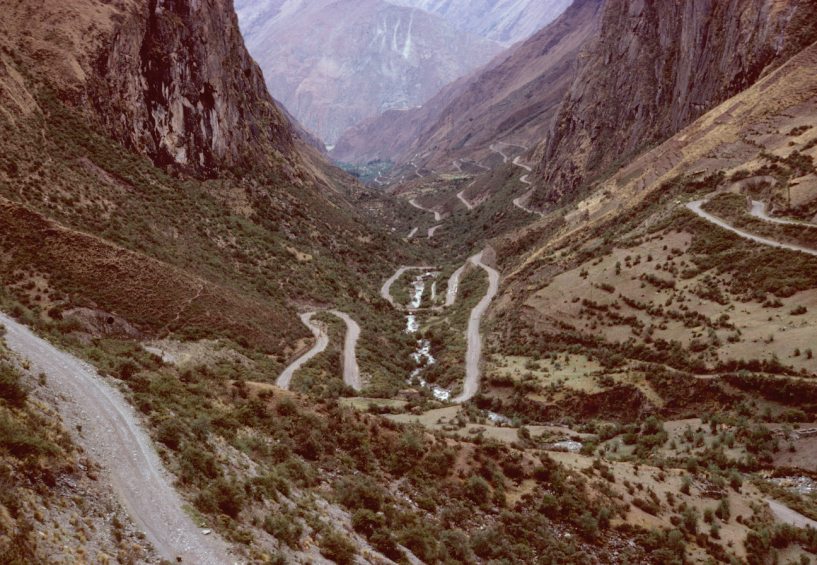

We could view this as progress. The land is now adapted to support humans, not bears and monkeys. However the land is not static. Every year it is pelted with meters of rain. With less vegetation holding the topsoil, it is washed downstream. The compaction of the soil on steep slopes by livestock enhances soil run off. Tropical soils are only fertile in the top layer. Once that layer is removed, the leached land underneath has less ability to nourish root growth to hold it in place, such as this valley in La Convención that once supported a forest.

Farmers in these regions travel farther and farther on foot and horseback to obtain wood for their cooking fires. I came across many families that had taken their children out of school for their help in getting firewood. Below a farmer carries a heavy load phad to use is a zig zag trail people use to procure wood in the ravine thousands of feet below by the Marañon River in Central Peru.

Soil erosion in the highlands effects water use all the way to estuaries. In 1983, a decade of deforestation in the highlands above the National Park of Amboró (Bolivia) resulted in floods that destroyed 2/3 of the arable land that sustained inhabitants of Santa Cruz.

Flooding causes disease from poor sewage treatment, it knocks out roads and hydroelectric plants, and clogs shipping lanes with sediment. Andean governments recognize that preserving ceja forests is a matter of national security. Fewer than 10% of these forests survive in much of the Andes.

When I started field work, there were fourteen national parks that protected populations of spectacled bears. Twenty-one years later in 1998, there were 58 parks with bears, many of them being colonized by people who have no other means of survival. In that short time I have seen whole valleys of forest wiped out and species go extinct. This much is clear. The future of civilization as we know it depends on maintaining this natural sponge that can soak up moisture and liberate it in manageable amounts for future generations of both bears and humans.