My colleagues say it is the natural behavior I express in my animal subjects that makes my origami different from that of other folders. I like to tell little stories in paper, not just make something recognizable. I pose them in the moment, as they react to danger, or wake up from a nap, and based on my observation of them during my career as a field biologist.

A standard way to make a paper animal is to fold a flat symmetrical model, and then shape its body and limbs to be more lifelike. Often the model at this stage has limited dimension and range of motion. My models are both 3 dimensional and often asymmetrical earlier in the folding process, to achieve a more lifelike result than most origami models. This sculptural approach requires that I put folds “right about here,” without obvious references, because it looks right, not because edges line up.

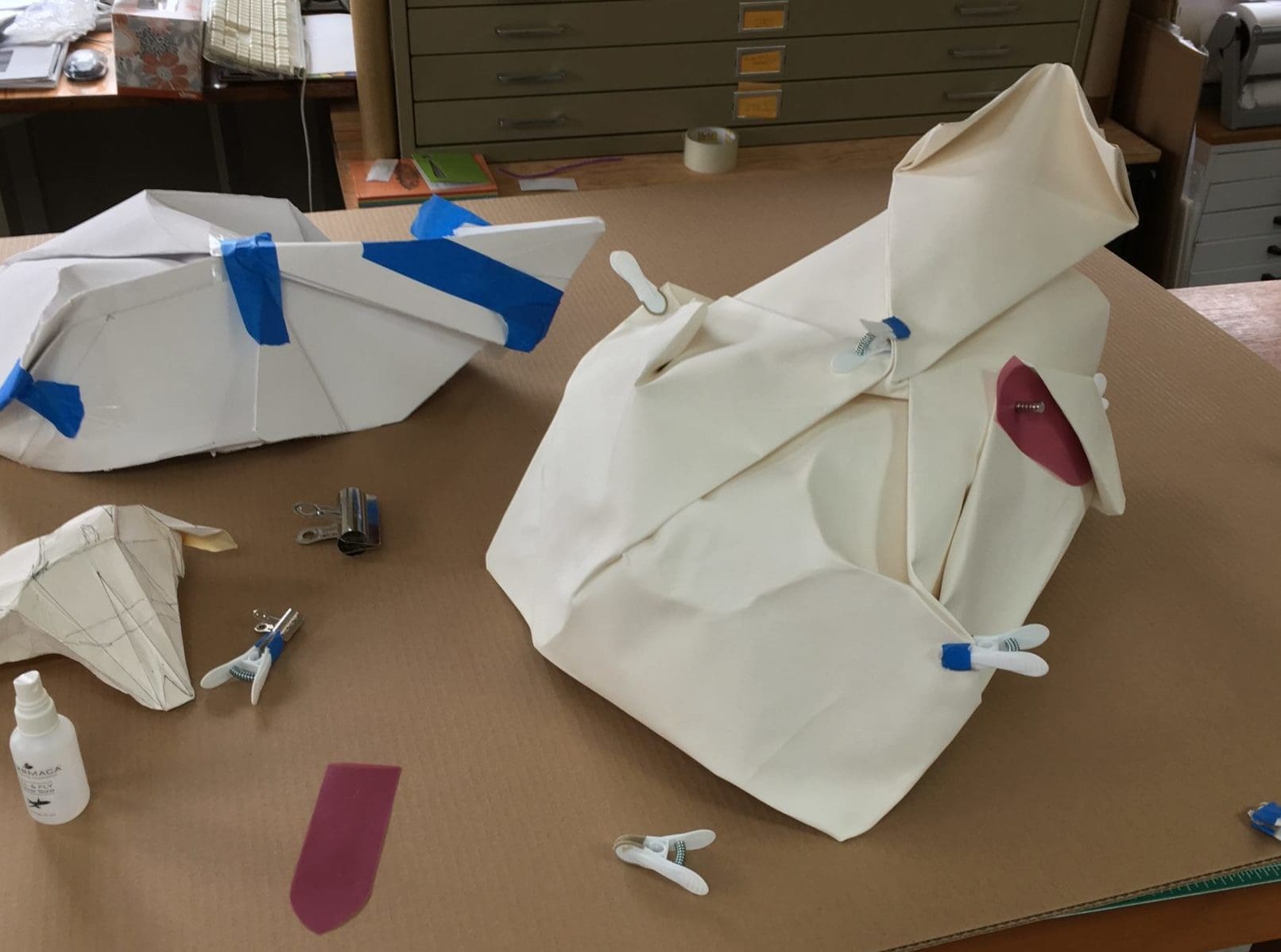

I fold with wet paper, in the tradition of Akira Yoshizawa, the father of modern origami and originator of the wet-folding technique. This allows me to use thick paper for more permanent sculpture when it is dry. After a decade with many failures, I have perfected wet-folding techniques to allow me to do large-scale origami like the mother polar bear and cub that is wet-folded from a single uncut square of Arches water color paper 112 cm to a side.

The process is very organic and risky for failure. To make the mother and cub I soaked a rectangle of Arches water color paper in the shower and then shaped it quickly with soft rounded creases using a small dry paper template to guide where to put folds by eye. The paper reacted more like clay as it dried after subsequent folds. The hand I placed inside the model was shaped like the forms I wanted the surface to express, while my other hand pressed creases gently into place, much the same way a ceramicist shapes a pot on a wheel. The model was dried and clamped into shape multiple times over a period of a week until I was satisfied with the result.

Many origami designers are driven to create increasingly complex models with appendages that come out of the paper edges. What intrigues me most are curved surfaces I create out of the middle of the paper. Instead of becoming more complex, my creations have fewer and fewer folds. This is because the real strength of origami in my view is in its inherent simplicity.

Most of my models have a different color on each side of the paper, meaning that they show both the top and the underside color. These “bi-colored” models are harder to design. To change color in a feature, either paper edges or corners have to be turned over, or the interior has to be expressed somewhere. Both measures are used to produce these owlets.

The paper for my earlier bi-color designs was made from two separate sheets of paper glued together. This limited me to the colors that were commercially available. In the past 15 years I have colored paper with ink applied by a sponge, charcoal dust rubbed into the surface from a rag (as in the kiwi above), and paint mixed with a variety of agents applied with my fingers. Finally my color palette is limitless!

The habitat and its requirements for the survival of my study animals were the central focus of my scientific research, and consequently a very important part of telling the stories about my folded animals. Designing habitat out of paper enabled many of my pieces to be hung on walls or to stand more than a meter tall, but only after years of solving technical problems. Solutions included coating paper with plastic resin (sockeye salmon stream bed depicted above), and including armatures of wood or metal to allow large pieces to maintain their shape. Some purists would say that only one uncut square that is folded without any surface treatment is allowed in origami. Most of my designs meet this definition. When I do something different it is for a reason to make art that will last for decades. I let the image justify its making and I always list the materials it is made from.